Viewpoints | May 11,2024

Apr 13 , 2025

By Mariana Mazzucato , Rainer Kattel

Governments and startups may share a thirst for innovation, but their goals diverge sharply. Startups focus on rapid iteration and financial returns, often solving specific problems with specialised solutions. The startup model's allure risks simplifying complex issues, confining solutions to short-term gains, and overlooking larger systemic barriers, argue Mariana Mazzucato, a professor in the economics of innovation and public value at University College London, and Rainer Kattel, deputy director of innovation and public governance at the UCL Institute for Innovation & Public Purpose. This commentary is provided by Project Syndicate (PS).

Around the world, governments are trying to reinvent themselves in the image of a business. Elon Musk's Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) crusade in the United States is quite explicit on this point, as is Argentina's chainsaw-wielding President, Javier Milei. But, one also hears similar rhetoric in the United Kingdom, where Cabinet Office Minister Pat McFadden wants the government to foster a "test-and-learn" culture and move toward performance-based management.

The problem is that governments and businesses serve vastly different purposes. If public policymakers start mimicking business founders, they will undermine their own ability to address complex societal challenges.

For startups, the highest priority is rapid iteration, technology-driven disruption, and financial returns for investors. Their success often hinges on solving a narrowly defined problem with a single product, or within a single organisation. Governments, by contrast, should tackle complex, interconnected issues like poverty, public health, and national security. Each challenge calls for collaboration across multiple sectors, and careful long-term planning.

The idea of securing short-term gains in any of these areas does not even make sense.

Unlike startups, governments are supposed to uphold legal mandates, ensure the provision of essential services, and enforce equal treatment under the law – more important today than ever. Metrics like market share are irrelevant, because the government has no competitors. Rather than trying to "win," it should focus on expanding opportunities and promoting the diffusion of best practices. It should be long-term minded, while achieving nimble and flexible structures that can adapt.

Introducing a new digital health app within a weak healthcare system may offer incremental improvements, but it will not address underlying systemic issues, like a shortage of medical workers or geographic challenges. Worse, if startup logic is applied to public services, it could lead to piecemeal solutions that exacerbate existing inefficiencies. For example, a city might create an app to report potholes, gaining quick wins in citizen engagement. However, this does not help the city to consider more sustainable transportation systems and lower carbon emissions that impact citizens' health.

The process by which governments learn to deliver better outcomes is profoundly different from that of a startup. Rather than blindly embracing startup culture, governments should examine past efforts to modernise and reform public services. There are several lessons to be learned.

The public sector needs a new foundation in economics. The prevailing model's emphasis on "efficiency" too often confuses outputs (how many school meals were subsidised?) with outcomes (how nutritious and sustainably or locally sourced were the meals?), and it rests on an overly simplified public-private dichotomy. The result is an overreliance on superficial heuristics like cost-benefit analysis, which does not necessarily measure progress toward desired systemic outcomes.

Governments also need to improve how they account for the long-term value of public investment.

For example, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves is right to shift the focus from the public sector's net debt to its net financial liabilities, which better recognises the return on public investments by including illiquid assets (government loans) and other financial liabilities (monetary gold). But, Reeves' scheme still does not reflect the value of non-financial assets (like government ownership of infrastructure and housing), and its short-term horizon prevents it from creating an incentive structure for longer-term investments.

Another lesson is that diversity is an asset, not an exercise in political correctness. Over the past century, the public sector strived for universality and uniformity: services should be as good and as accessible in small towns as they are in wealthier cities. But, how those services are delivered also matters. Creating an adaptive, outcomes-focused public sector requires a more diverse workforce, ongoing training, multiple analytical perspectives, and a portfolio of interventions (since there are no silver bullets).

The public sector needs to strike a balance between its political, policymaking, and implementation capabilities. Governments are more than administrative machines; they require political leadership, a sense of purpose, and the ability to adjust policies. Too often, public-sector reform focuses on technocratic efficiency, while neglecting the need to articulate and execute on a vision that will win public support.

Some municipal leaders have been pioneering new models. Rather than focusing on the politics of grievance, for example, mayors from Barcelona to Bogotá have been elected on platforms of urban transformation. Their success proved the importance of balancing political vision with feasible implementation.

More broadly, to equip the public sector with the capacity it needs to address contemporary challenges, governments – and what one of us has called "entrepreneurial state" – should cultivate six capabilities that will enable them to learn, adapt, and adjust. The first is strategic awareness: an ability to identify emerging challenges and opportunities proactively. The second is agenda adaptability, so that priorities can be balanced while responding to crises. The third is coalition-building and partnerships, so that the public sector can foster collaboration across sectors and with communities.

The fourth capability is self-transformation: the continual updating of public agencies' skill sets, organisational structures, and operational models. This presupposes a fifth capability: experimentation and iterative problem-solving in public-service delivery. And, lastly, the public sector needs outcomes-oriented tools and institutions.

Building such capabilities across the public sector requires rethinking public-service training, competency frameworks, and organisational models. Above all, however, it means rethinking how we measure and assess the public sector's work. That is why we at the UCL Institute for Innovation & Public Purpose (IIPP) are creating a Public Sector Capabilities Index, to evaluate government capabilities at the city level. Such tools can identify gaps in skills or resources, while linking capability development to better outcomes.

Governments should not be run like startups, because they serve vastly different purposes, answer to different constituencies, and operate on entirely different timelines. Rather than chasing a Silicon Valley mirage, policymakers should focus on building the structures and capabilities that enable governments to be responsive, resilient, and effective. (Alongside our work at the IIPP, others, like Jennifer Pahlka and Andrew Greenway at the Niskanen Centre, have offered further visions of what this could look like.)

Reform should be rooted in a deep understanding of public-sector dynamics, rather than in the desire to mimic unicorns chasing the next big disruption, too little too late. And yes, we are learning in real time that disruption alone is a recipe for disaster.

PUBLISHED ON

Apr 13, 2025 [ VOL

26 , NO

1302]

Viewpoints | May 11,2024

Viewpoints | Nov 02,2024

Fortune News | May 13,2023

Commentaries | Sep 06,2020

Agenda | Apr 22,2023

Commentaries | Jan 18,2019

Money Market Watch | Apr 13,2025

Fortune News | Apr 25,2020

Viewpoints | Nov 02,2024

Viewpoints | May 18,2024

My Opinion | 128690 Views | Aug 14,2021

My Opinion | 124938 Views | Aug 21,2021

My Opinion | 123020 Views | Sep 10,2021

My Opinion | 120834 Views | Aug 07,2021

Dec 22 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Charged with transforming colossal state-owned enterprises into modern and competitiv...

Aug 18 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

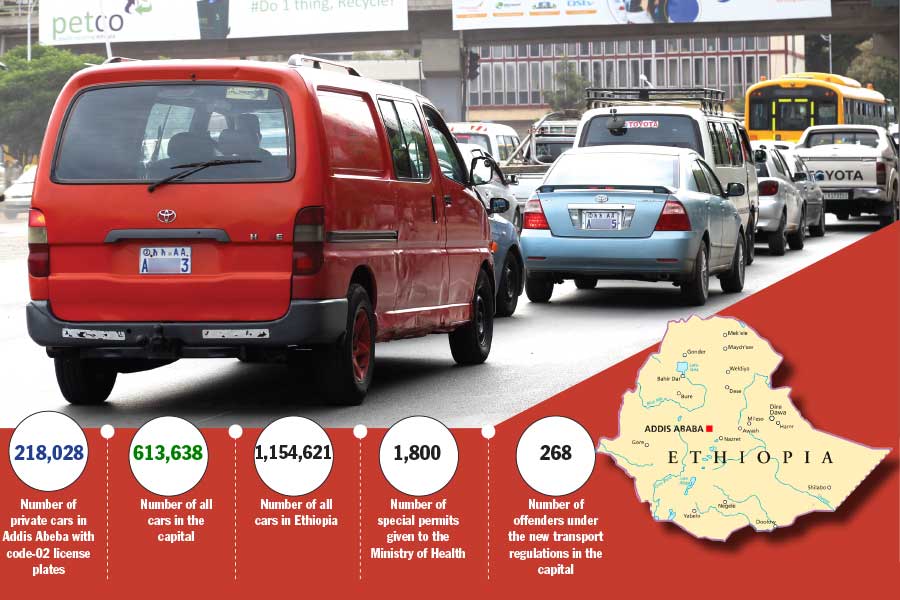

Although predictable Yonas Zerihun's job in the ride-hailing service is not immune to...

Jul 28 , 2024 . By TIZITA SHEWAFERAW

Unhabitual, perhaps too many, Samuel Gebreyohannes, 38, used to occasionally enjoy a couple of beers at breakfast. However, he recently swit...

Jul 13 , 2024 . By AKSAH ITALO

Investors who rely on tractors, trucks, and field vehicles for commuting, transporting commodities, and f...

May 3 , 2025

Pensioners have learned, rather painfully, the gulf between a figure on a passbook an...

Apr 26 , 2025

Benjamin Franklin famously quipped that “nothing is certain but death and taxes.�...

Apr 20 , 2025

Mufariat Kamil, the minister of Labour & Skills, recently told Parliament that he...

Apr 13 , 2025

The federal government will soon require one year of national service from university...

May 3 , 2025

Oromia International Bank introduced a new digital fuel-payment app, "Milkii," allowi...

May 4 , 2025 . By AKSAH ITALO

Key Takeaways: Banks face new capital rules complying with Basel II/III intern...

May 4 , 2025

Pensioners face harsh economic realities, their retirement payments swiftly eroded by inflation and spiralling living costs. They struggle d...

May 7 , 2025

Key Takeaways Ethiopost's new document drafting services, initiated in partnership with DARS, aspir...